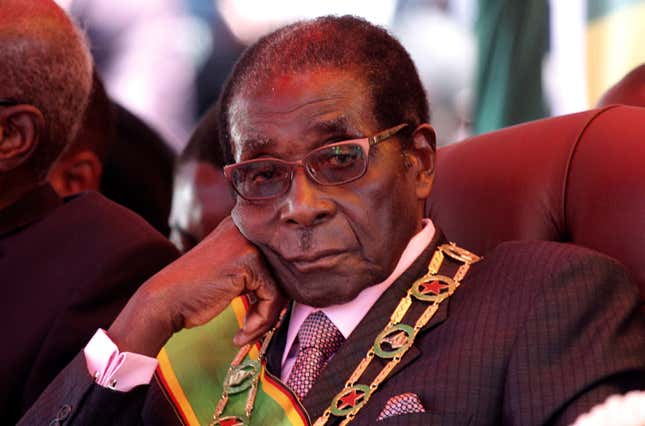

Robert Gabriel Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s first post-independence leader, has died aged 95.

News of Mugabe’s death has been confirmed by his successor and current Zimbabwe president, Emmerson Mnangagwa. The former ruler died in a Singapore hospital where he was reportedly seeking treatment. Singapore was Mugabe’s most frequent foreign destination since 2016 as he increasingly sought health checks.

Mugabe’s passing comes nearly two years after he was ousted from office in a coup following a 37-year rule which ranks him among Africa’s longest serving leaders. Mugabe’s resignation from office came after days of pressure from military officials. The former president spent his post-presidency years between seeking treatment, facing a government probe and attempting to wield some political power.

A tainted legacy

In death, Mugabe will be remembered for several things, ranging from one extreme to another, as many people within and outside Zimbabwe remain conflicted over his legacy.

The first half of Mugabe’s lifetime will see him remembered as a powerful, fierce voice of liberation for Zimbabwe, playing a key role in the country’s independence from colonialists at some personal cost. Such was his popularity that he won the country’s first post-independence election in a landslide. He is still remembered across Africa as a liberator and comrade in the fight against colonial rule.

As Quartz Africa wrote at the time of his removal from office in 2017: Mugabe’s birthday, Feb. 21, has been marked for years by a boisterous youth movement with lavish parties. But his beginnings were much more modest. He was born in 1924, the third child of a carpenter and catechism teacher, in the Matibiri village in the Zvimba district of what was then known as Southern Rhodesia. The family was impoverished, and his father left when he was only 10.

Mugabe was a gifted student and his education was supported by missionary teachers. He became a teacher to support his family, which influenced his later decision to prioritize education after independence (as president, he would go on to spend nearly eight times more on education than neighboring countries). At 25, he received a scholarship to attend the University of Fort Hare in South Africa, the alma mater of several of southern Africa’s liberation icons, including Nelson Mandela. There Mugabe mingled with activists Julius Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, who would later be elected presidents of Tanzania and Zambia respectively.

After his introduction to Marxism and pan-Africanism at Fort Hare, Mugabe moved to Ghana, the first African country to achieve colonial independence. While teaching high school and completing a Bachelor of Administration degree, he met with independence-era president Kwame Nkrumah. He also met his first wife, Sarah Francesca Heyfron. The couple were married from 1961 until her death of kidney failure in 1992.

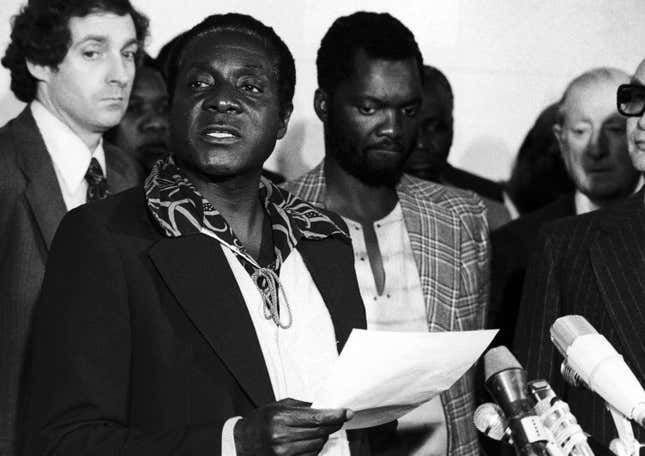

The Liberator

Mugabe returned in 1960 to a Zimbabwe where black people’s rights were rapidly shrinking under a group of right-wing white leaders. His political legacy is built on his opposition to this minority rule. As a secretary of the National Democratic Party and editor of the party’s newspaper, The Democratic Voice, he first began to agitate for black rule in the early 1960s. He later joined the Zimbabwe African People’s Union, led at the time by Joshua Nkomo. Mugabe and other activists were subsequently jailed by then-Prime Minister Ian Smith, notorious for running in 1964 under the ticket of “a whiter, brighter Rhodesia.”

In jail, Mugabe split from Nkomo to become the leader of the Zimbabwean African National Union (Zanu). He was released in 1974, unusually, at the insistence of South Africa’s apartheid government, and allowed to attend a conference in Zambia. From there, he escaped to Mozambique to join the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army, which was facing off against the colonial government in what came to be known as the Rhodesian Bush War, or Chimurenga (Shona for “revolutionary struggle”). This fierce series of battles, from 1964 to 1979, saw at least 20,000 people killed. It ultimately led to victory (pdf) for the liberation army in the form of the country’s first democratic elections, which Mugabe’s Zanu won in a landslide.

It is these struggle credentials that many around the continent cling to when they laud Mugabe. But in doing so, they have turned a blind eye to the continued suffering of Zimbabweans. Mugabe also frequently used his past, and the spectre of white, Western influence, to remind Zimbabweans where their true freedom comes from. His paranoid, conspiratorial quips about Western leaders like George Bush and Tony Blair are often reported on by international outlets. Less so the fact that thousands of Zimbabweans now face starvation and that half the country has no access to proper schooling.

Like Mugabe, many Zimbabweans blame his tainted legacy and the country’s economic collapse on European and US sanctions (it doesn’t help of course, that the only time the West has properly intervened was when white Zimbabwean farmers were in danger). Mugabe, however, has always been problematic.

Upon his death, president Mnangagwa has hailed Mugabe as “an icon of liberation…who dedicated his life to the emancipation and empowerment of his people.”

But given years years in power, especially in the latter half of his life, Mugabe may also be remembered very differently as the one-time liberation hero morphed into an oppressive autocrat with a seeming iron-grip on power. His government faced accusations of human rights abuses with critics jailed and free press stifled.

Mugabe also presided over a devastation of Zimbabwe’s once promising economy, with his populist policies resulting in stunted growth a practically useless currency. A recurring sign of his fall from reverence were the frequent protests against his government which marked his last years in office. Ultimately, public dissatisfaction and anger provided the basis for the military coup which essentially removed Mugabe from office in November 2017.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox